Florida Freeze Prompts Roundup of Cold-Stunned Iguanas as Thousands Fall From Trees

By LUKE FUNK

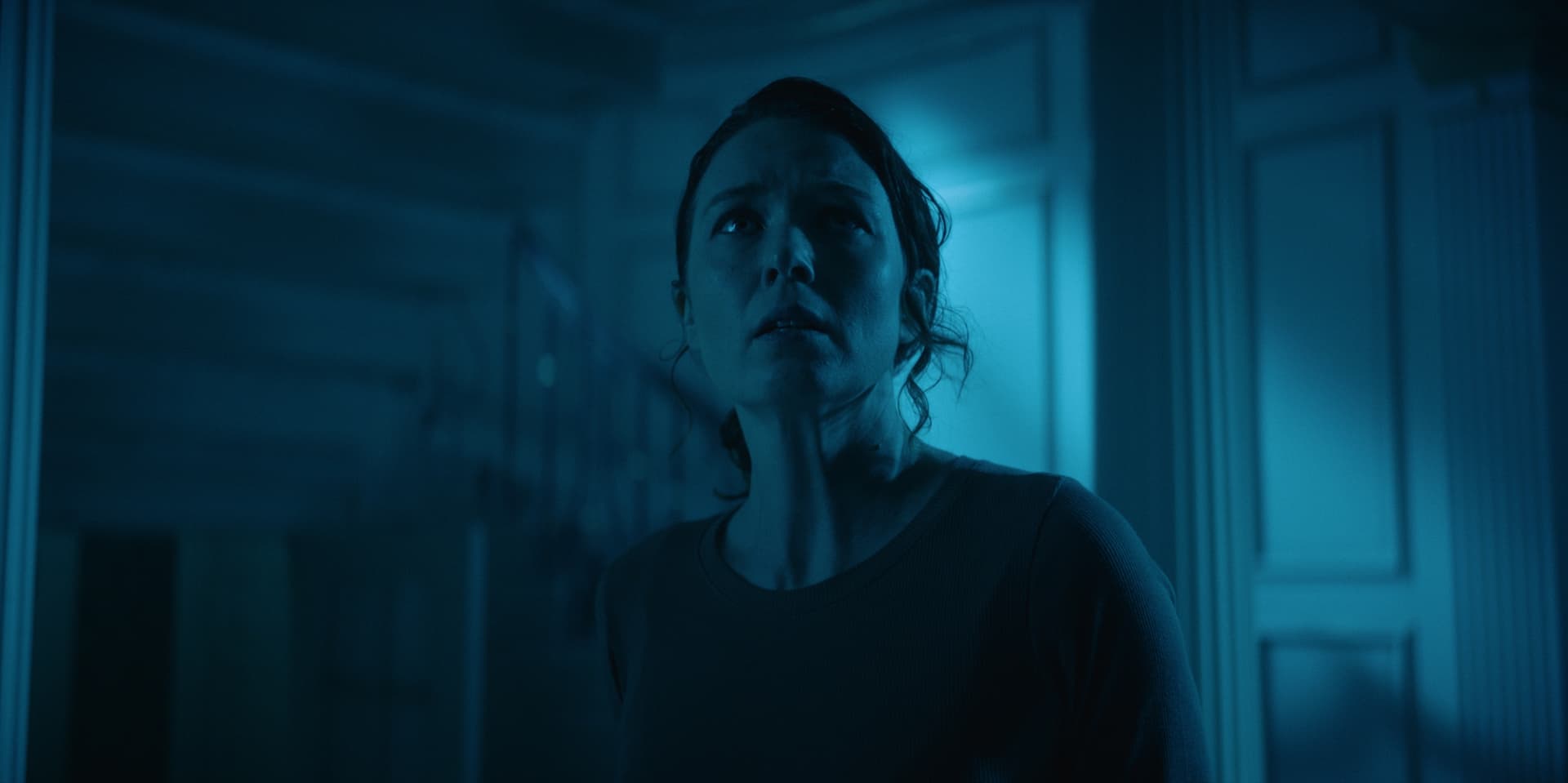

|‘The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel’ is practically the only show I enjoy so much that I do the opposite of binging: I try to take as much time as possible to watch every episode.

Already have a subscription? Sign in to continue reading

$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

By continuing you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.

By LUKE FUNK

|

By THE NEW YORK SUN

|

By LAWRENCE KUDLOW

|

By THE NEW YORK SUN

|

By BENNY AVNI

|

By SHARON KEHNEMUI

|

By BRADLEY CORTRIGHT

|

By MARIO NAVES

|