David Lynch Experimented With American Culture: Without Him, American Culture Would Be a Lot Less Weird

No artist felt more American than this mysterious surrealist.

David Lynch’s intense interest in art began with paintings and sculptures. His interest in the movement of sculptures inspired him to make short films. This led him to direct his first feature, “Eraserhead,” which introduced a whole new style – absurd and abnormal – to film. From his TV series “Twin Peaks” to his cinematic efforts such as “Blue Velvet”, “Lost Highway” and “Mulholland Drive”, Lynch has left his mark – weird and experimental – on multiple generations of popular culture.

Unsurprisingly, not everyone reacted to him with open praise. Lynch’s adaptation of Frank Herbert’s novel “Dune” was an infamous and old-fashioned clash between meddling studio executives and an auteur, feuding over a story that was probably impossible to tell in a two-hour film. From when the movie bombed, in 1984, until 2021, Herbert’s book was deemed “unfilmable”.

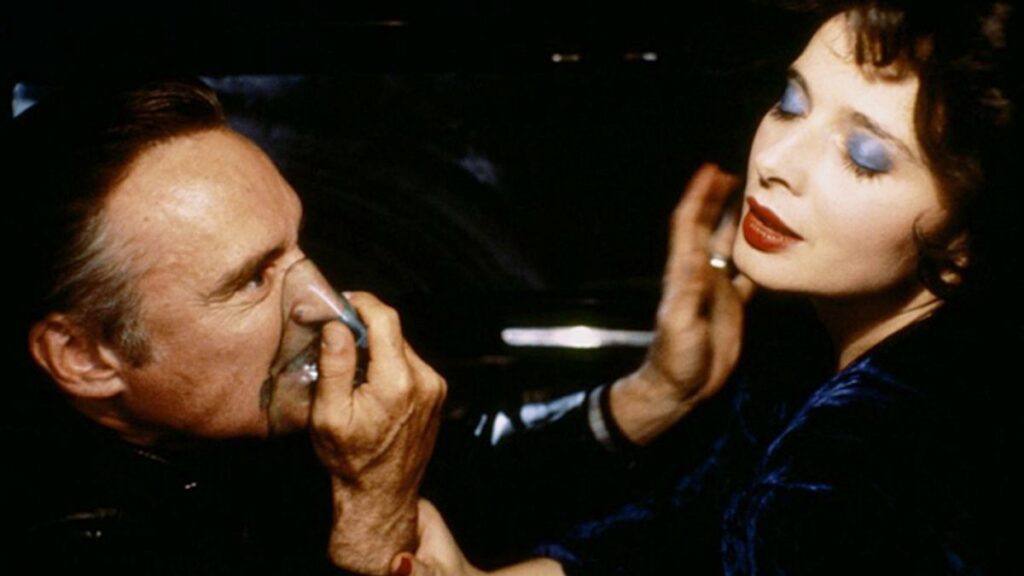

The late film critic Roger Ebert was far from Lynch’s biggest champion, often lambasting the filmmaker for what he considered misogyny (he particularly hated “Blue Velvet”, claiming that Lynch had exploited Isabella Rossellini in a scene where her character is depicted in the nude, being battered by Dennis Hopper’s Frank Booth (Ms Rossellini, who dated Lynch in the 1980s and remained close with him for the rest of his life, said in a recent interview that she was surprised by Ebert’s reaction, considering that she was 31 at the time).

While it’s understandable to feel alienated by the toxicity in Lynch’s works – the characters get erratic and the narratives become illogical – there is genuine truth and heart beneath them. Lynch highlights the darkness of American suburbia not by portraying it directly, but by teasing the viewer with visual cues.

Perhaps Lynch’s greatest film, “Mulholland Drive”, does exactly that. To say that its story is about an aspiring actress striking a friendship with an amnesiac movie star oversimplifies a film that Lynch’s fans revere but that left many more casual viewers completely confused. When the film was released on DVD, Lynch suggested viewers pay attention to clues in the opening credits, to study the red lampshade. But “Mulholland Drive” isn’t a mystery that can be, or needs to be, solved. Its confounding nature is its biggest strength. Even Ebert, who gave the film a glowing review after years of lambasting Lynch, felt that “there may not be a mystery.”

The term “Lynchian” is spoken in the same way that the terms “Spielbergian”, “Kubrickian” and “Hitchcockian” denote the directors’ influence on the arts. What makes a “Lynchian” film distinct isn’t simply the weirdness and the creepy mood that we associate with his work. It’s that Lynch’s style challenges our subconscious and tricks us into accepting his altered and contorted reality. When he introduced “Twin Peaks”, his television masterpiece, to Japanese viewers he said “We are like the dreamer who dreams, and then lives inside the dream. But who is the dreamer?”

Distilling this intent are some notable needle drops. In “Blue Velvet”, it’s Dean Stockwell lip syncing to Roy Orbison’s “In Dreams”. In “Wild at Heart”, it’s Nicolas Cage singing Elvis Presley’s “Love Me”. These scenes are hypnotic and strangely terrifying, but also make you feel that you are in a different world.

Mr Lynch’s style has been imitated by other filmmakers, but what they miss is his personal attachment to the past. You can find that in his most conventional films, “The Elephant Man” and “The Straight Story”, both outliers detached from his work as a surrealist. “The Elephant Man” is a simple biopic of a deformed man wanting to be accepted in society, whereas “The Straight Story” was based on the true story of Alvin Straight, traveling by his tractor to visit his estranged brother. The latter has a distinct American character that Lynchheads would be familiar with; screenwriter Mary Sweeney, his frequent collaborator, describes it as “stoic, non-verbal, stubborn, idiosyncratic”. In hindsight, “The Straight Story” was less of a creative risk for Mr Lynch than it was for Disney, which produced the film (it was a commercial flop). It is far more courageous than say, last year’s “I Saw The TV Glow”, which apes the aesthetic and is too detached from humanity, forgetting the spirit of being Lynchian.

I must admit that I have not seen everything by Mr Lynch. I haven’t seen “Inland Empire” (his last feature film) or “Twin Peaks” (perhaps his most famous work, the reboot of which was his final artistic effort). By that time, around 2017, Lynch had commodified much of his personality as an experimental artist and had already told the stories that he wanted. Wracked by emphysema (he’d been a heavy smoker most of his adult life) and largely housebound, he died shortly after he had to evacuate his Los Angeles home due to the wildfires. By then, Lynch had already ended his journey. But what doesn’t end are his dreams. And we feel this every day.