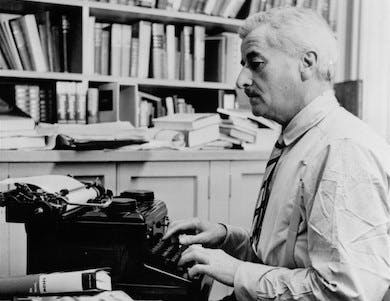

Nobel Prize Winner William Faulkner’s Battle With Grief

No matter his afflictions or his adultery, in the end he rededicated himself to his family and served his country as a distinguished literary figure traveling abroad under the auspices of the Department of State.

‘Between Grief and Nothing: The Passions, Addictions and Tragic End of William Faulkner’

By Lisa C. Hickman

McFarland, 315 Pages

Pathography is Joyce Carol Oates’s word for literary biographers who dwell on “dysfunction and disaster, illnesses and pratfalls, failed marriages and failed careers, alcoholism and breakdowns and outrageous conduct.” The word could apply to Lisa Hickman, who details dozens of William Faulkner’s breakdowns and hospitalizations, usually for what his doctors diagnosed as “acute alcoholism.”

Ms. Hickman also depicts a man fiercely devoted to the creation of great literature. No matter his afflictions or his adultery, in the end he rededicated himself to his family and served his country as a distinguished literary figure traveling abroad under the auspices of the Department of State.

Faulkner exemplifies Samuel Johnson’s declaration that the “heroes of literary as well as civil history have been very often no less remarkable for what they have suffered than for what they have achieved.” In Faulkner’s case, excessive drinking over decades became a kind of self-medication to ward off the pain of back injuries after repeated falls from horses, depressions after he had written some of the greatest works of American literature, and powerful letdowns after the drama and intrigue of affairs with women similar to the passionate characters of his fiction.

Ms. Hickman’s empathetic narrative palpably demonstrates that Faulkner deserved the devotion of an ever faithful — if exasperated — wife, editors, lovers, fellow screenwriters, and the professional caregivers in the Leonard Wright Sanatorium at Byhalia, Mississippi, where he was admitted many times and where he died.

If only Ms. Hickman had continued with that story, of a man strong enough to deal with his grief, instead of rehashing the details of Faulkner’s life that are derived mainly from a biography by Joseph Blotner published more than 50 years ago. Her dependence on this secondary source — even though it remains one of the bedrocks of Faulkner biography — is deeply unfortunate.

Not having done much primary research, Ms. Hickman makes several errors. To Blotner and other biographers, Faulkner’s account of wandering in Death Valley seemed like a tall tale, yet there are in the Berg Collection of the New York Public Library letters from a close friend with whom Faulkner stayed at Hollywood, Hubert Starr, confirming the novelist’s seemingly far-fetched explanation of why he did not show up for work at MGM.

Similarly, Ms. Hickman refers to Faulkner’s erotic drawings “sealed in the Berg Collection until 2039,” even though they are not sealed — I have seen them and commented on them in my biography of Faulkner. Those drawings graphically reveal a fervid Faulkner practically story-boarding his affair with script supervisor Meta Carpenter as though they were part of a pornographic movie.

Finally, Ms. Hickman, author of the excellent “William Faulkner and Joan Williams: The Romance of Two Writers,” mistakenly suggests that his affair with Jean Stein was not nearly as important as the fitful, ambivalent liaison with Williams, who wrote a novel, “The Wintering,” about her intimacy with him.

In fact, Faulkner’s attachment to Stein, another young woman just about to begin a writing career, was more fulfilling, more playful, and more gratifying to both of them than what he had experienced with Joan Williams, who never was able to reciprocate the depth of commitment that Faulkner sought from her. I know so because Stein’s papers at the New York Public Library show as much.

Ms. Hickman also repeats the view of Blotner and other Faulkner biographers that his Hollywood periods never meant that much to him. Faulkner abetted this belief, but it is not so.

He often began with complaints about the scenario work but ended up, in certain cases, quite enthusiastic about what he had been able to accomplish. For example, he writes to Joan Williams from Hollywood: “fantastic work.” Ms. Hickman does not pause to consider what he might mean, but if you look at his work on “The Left Hand of God,” you see a script that dovetails with his writing of a novel, “Requiem for a Nun,” both of which are about redemption.

Ms. Hickman has a good story to tell, but as Faulkner once said to a fellow writer, Shelby Foote, about his work: Next time do better.

Mr. Rollyson explores the affair between Faulkner and Jean Stein in a chapter of a forthcoming book, “Faulkner On and Off the Page: Essays in Biographical Criticism.”