Seamus Heaney Letters Collection Offers a Scoop of the Nobel Laureate — but No More

Unfortunately, the editor readily concedes to the censoring eye of the publishing powers that be as well as to the families of his subjects, who dictate what he can and cannot publish.

‘The Letters of Seamus Heaney’

Edited by Christopher Reid

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 848 pages

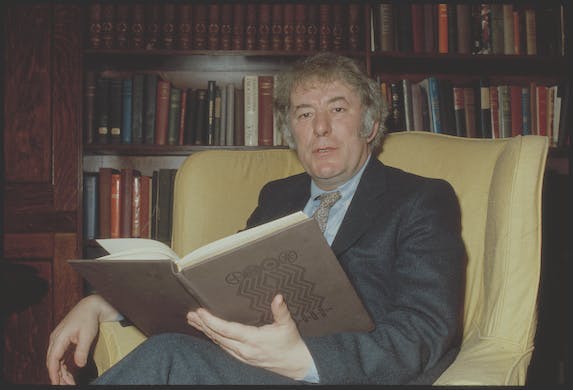

An Irish poet who was awarded the Nobel Prize, Seamus Heaney is an elegant and playful correspondent, amusing and generous. He is a joy to read — even in bits and pieces, if you don’t want to devour the whole volume. The editor has helpfully supplied annotations and introductions that explain certain allusions, events, and personalities that might otherwise baffle those not in the know.

Imagine what it was like to await one of Heaney’s letters — like the one on December 9, 1964, which begins: “Christmas had better be a time of good will if you are not to stop reading just about here.” How about this tempting opening, dated August 4, 1965: “I cannot enter a new life (wedding to-morrow at 10-30) without settling the sins of my past life.”

Those sentences were written when Heaney was at the start of an illustrious career. What about a decade later, when he is much further along and yet finding a career as a poet no less troubling and anxiety-prone, as he confides to a friend: “You’ll have been calling me all the shites in the world for not answering your letter of last month but until yesterday I had nothing to say except a pious hope that something would be done some time.” He sounds a little like a Dickens character, Mr. Micawber, if not quite as cheerful in expecting something to “turn up.”

The lilt and verve of Heaney’s letters is reminiscent of Synge’s “Playboy of the Western World.” Heaney was not one of those scandalous poets, like his friend Ted Hughes, with fraught marriages and affairs, but Heaney could dramatize himself as though he were so. That he wasn’t is evident in his empathy, his humorous supposition that one of his correspondents might be thinking of him as one of the “shites.”

A good bit of Heaney’s correspondence is about his teaching in America, on which he had to rely for an income. He had mixed feelings about the country, but almost always behaved as a good guest at the academic institutions that employed and honored him. If you want to assess Heaney’s judgment about America, turn to Edward O’Shea’s “Seamus Heaney’s American Odyssey.”

Heaney had none of Ted Hughes’s sneering rejection of the new world, which the latter had attached himself to in the figure of Sylvia Plath. Mr. Reid edited Hughes’s letters, and a sorry job he made of it by kowtowing to Hughes’s widow — who would have none of her husband’s epic philandering exhibited on the page.

Mr. Reid is what I’d call an “inside editor.” He was previously employed at Heaney and Hughes’s publisher, Faber & Faber. He readily concedes to the censoring eye of the publishing powers that be as well as to the families of his subjects, who dictate what he can and cannot publish.

In Mr. Reid’s introduction, he confesses that Heaney’s family members would not let go of their letters, and so we have no insight into Heaney’s youth, or his relationship with his family. Fortunately, though, the Reid-Heaney book does not have all those ellipses strewn about as in Mr. Reid’s edition of Hughes’s letters, making for much cogitation about what was left out.

The gold standard is “The Letters of Sylvia Plath,” by which virtually all collections of correspondence are to be measured. The editors, Karen Kukil and Peter K. Steinberg, include every letter she ever wrote, save those that are lost and, in a few instances, some that could not be pried away from their possessors. No one hovered over the editors, telling them what they could or could not publish.

Nearly all collections of letters are “selected,” which makes them sort of skewed biographies. Of course, biographers have to make selections too, but if they are acting in good faith they do not omit, say, the subject’s childhood or love affairs.

So, enjoy the Heaney letters for their wonderful language, though be aware that punctuation has been regularized in most cases, and so much of the raw material — the misspellings and eccentric punctuation — has been excised. As Mr. Reid admits, Heaney has been put through the publisher’s “house style.” So don’t suppose you will find therein the whole man.

Mr. Rollyson is the author of “Confessions of a Serial Biographer.”