Can America End Tehran’s Nuclear Aspirations Without Boots on the Ground?

By BENNY AVNI

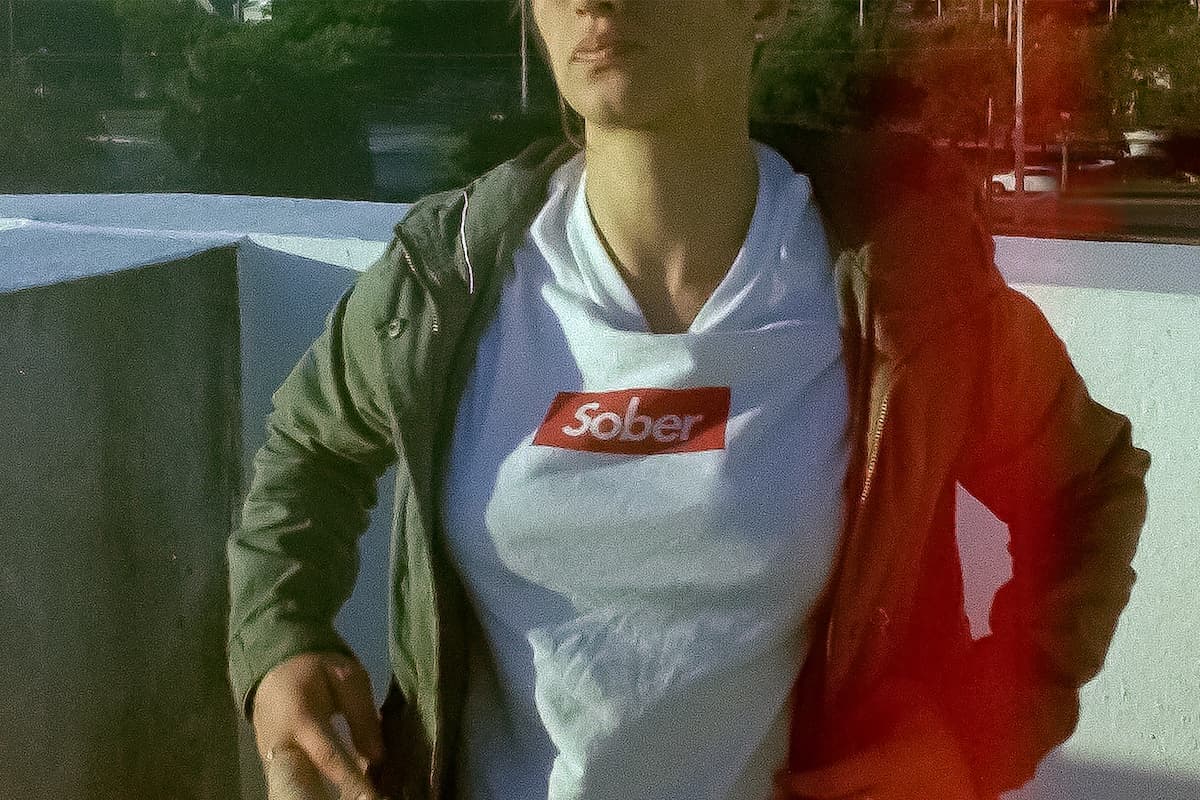

|Hearing how some centers treat addicts as commodities, a recovering alcoholic sets forth to examine fraud, profiteering, and malpractice utilizing his filmmaking experience.

By BENNY AVNI

|

By BRADLEY CORTRIGHT

|

By MATTHEW RICE

|

By BRADLEY CORTRIGHT

|

By A.R. HOFFMAN

|

By BRADLEY CORTRIGHT

|

By DONALD KIRK

|

By CARL ROLLYSON

|Already have a subscription? Sign in to continue reading

$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

By continuing you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.