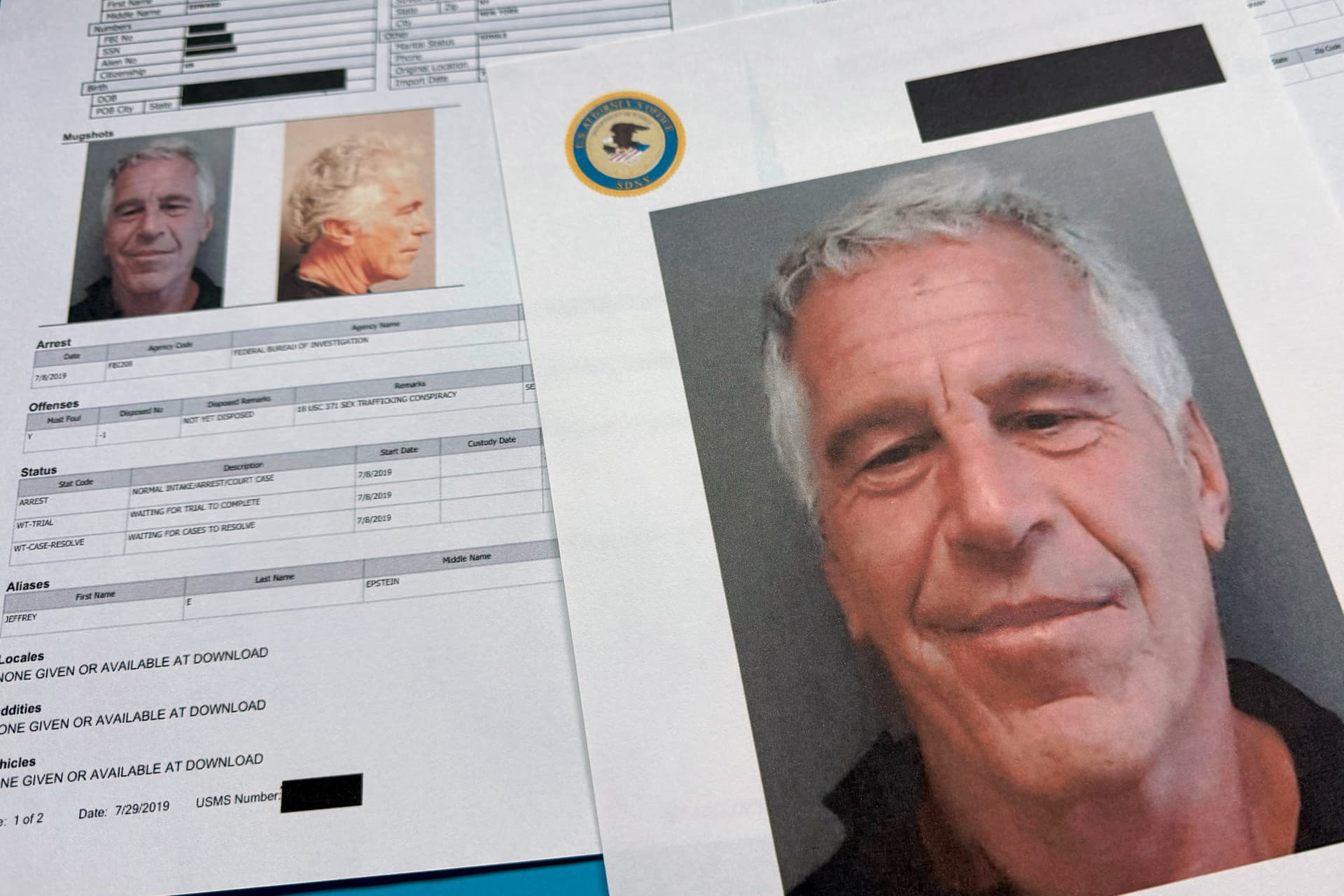

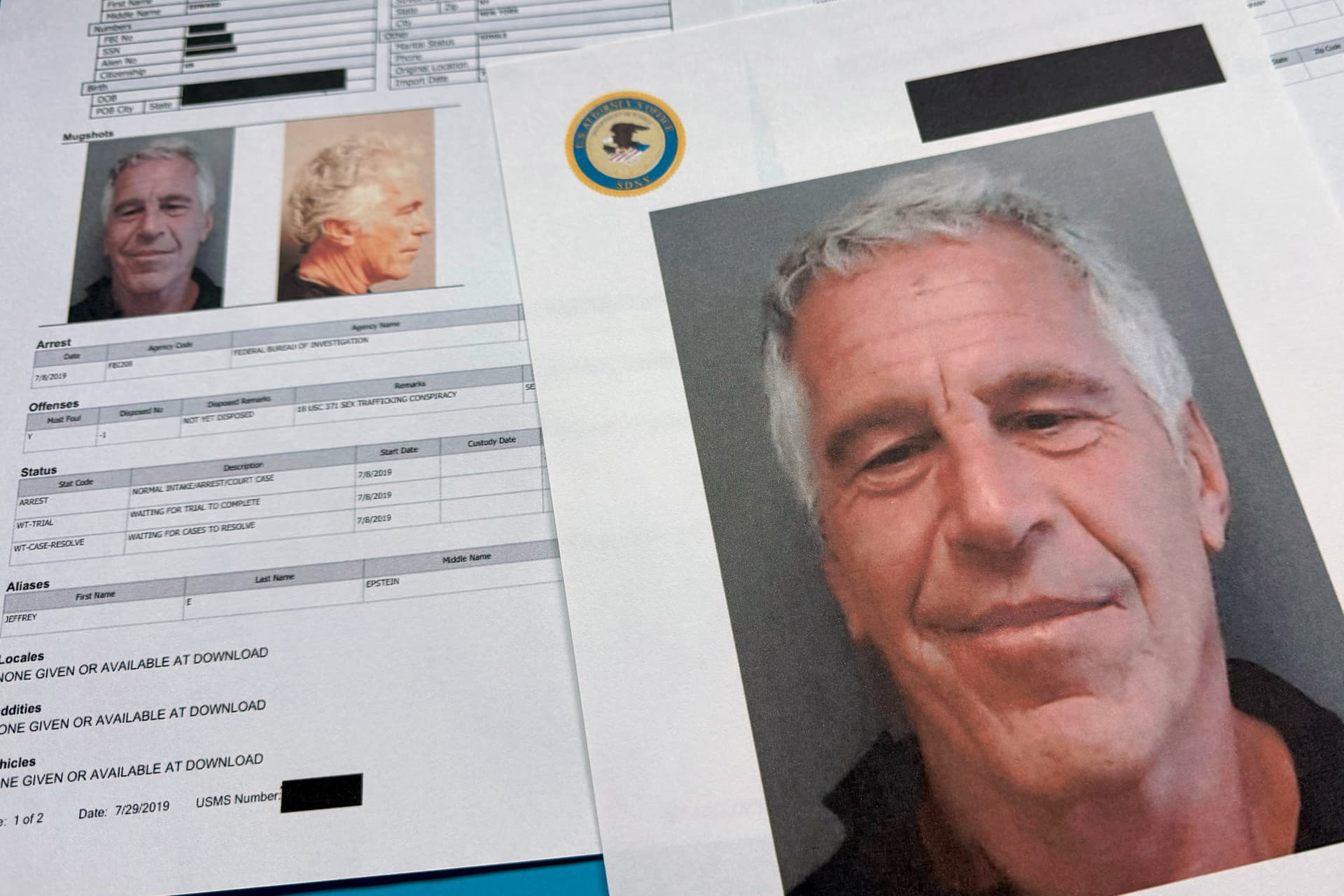

Final Release of Epstein Files Details Ties to Tech Titans and Top Officials but Fails To Satisfy Critics

By JOSEPH CURL

|Litterateurs may not like that vulgar expression, but part of Hemingway’s modernness was his understanding of mass media and of how hard the writer has to work to stay in the public’s consciousness.

Already have a subscription? Sign in to continue reading

By JOSEPH CURL

|

By JAMES BROOKE

|

By CAROLINE McCAUGHEY

|$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

By continuing you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.