Only the Greatest Form of Flattery Has Diminished ‘The 400 Blows’

With its much imitated ending, Truffaut’s 1959 movie is an uncanny, often funny, and ultimately heartbreaking evocation of adolescence and its complications.

With the recent death of Jean-Luc Godard, French cinema of a certain stripe has of late received more mainstream attention than in years.

You remember La Nouvelle Vague, of course: that cadre of heady young men centered around the influential journal Cahiers du Cinéma who went on to become filmmakers and, or so it has been argued, changed the way movies were made. Certainly, their names resonate with cinephiles: along with Godard, these include Éric Rohmer, Claude Chabrol, Jacques Rivette, and Francois Truffaut.

Godard’s 1960 film “Breathless” was his debut and his breakout, and he had help putting it into shape: Chabrol lent a hand, as did Truffaut. The latter was coming off “The 400 Blows,” his own initial foray into feature films, and, in the end, the most commercially successful effort in his native land.

“The 400 Blows” has been on the calendar at Film Forum for some time, so its current revival isn’t due to any particular reason other than the picture’s enduring quality. The good people at West Houston Street are touting the movie as “one of the most stunning directorial debuts in film history,” all but challenging New Yorkers, a population ever eager to voice opinions, to argue otherwise.

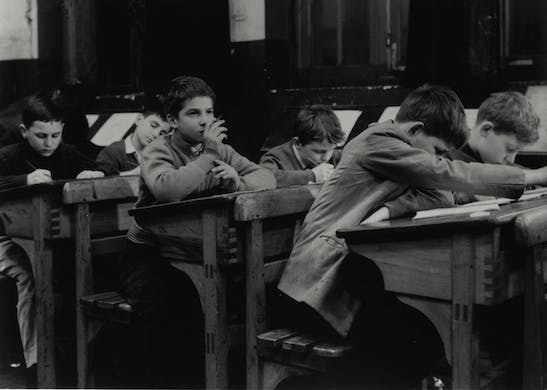

Good luck with that. Some 60 years after the fact, Truffaut’s movie remains an uncanny, often funny, and ultimately heartbreaking evocation of adolescence and its complications. Typically described as a coming-of-age story, “The 400 Blows” is, in actuality, its antithesis. As embodied by Truffaut, the saga of 15-year old Antoine Donel (Jean-Pierre Léaud) purposefully sets out to frustrate the audience’s expectations about just how thoroughly wisdom — or something like it — can be gleaned from experience.

“The 400 Blows” is, famously, a film without resolution. The stilled image that ends the picture — in which our protagonist, after running to the ocean, looks directly at the camera and, by fiat, the audience — has been replicated any number of times, from “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” and “Harold and Maude” to a host of lesser ventures, including, if memory serves, “Back to School,” with Rodney Dangerfield.

Time and distance temper innovation. Whatever power the freeze-frame ending might once have possessed, it has since been diminished by the cliches that were subsequently set into motion. If anything, the immediate lead-up to the conclusion of “The 400 Blows” — wherein Antoine runs without cease in an expansive traveling shot — is more impressive because of the existential crisis it so thoroughly embodies. Moving pictures should, after all, move.

Is there anything left to be said about a film that has been as adored and dissected as this one? The current revival helps us to take stock of the film’s staying power, and its familiarity allows for our focus to settle on tangents that might otherwise receive short shrift.

What, for instance, are we to make of the views of Paris seen under the opening titles? As the camera skitters along, we see the Eiffel Tower, not in full, but obscured and in the distance, a ghostly presence forever out of reach. Henri Decaë’s black-and-white cinematography forgoes strong contrasts for an array of grainy middle-grays, as if the depicted events are being viewed through the scrim of memory.

Which they were, of course. Truffaut predicated the storyline on his own childhood, but the true magic of “The 400 Blows” owes as much and, probably more, to Mr. Léaud. Forget “performance”: Mr. Léaud occupies the screen — magnetizes it, really — in a way that most actors only dream of achieving. Precious few are the movie characters who have as rich an interior life as Antoine.

Truffaut would make four additional films following up on the life and adventures of Antoine — “Antoine and Colette,” “Stolen Kisses,” “Bed and Board,” and “Love on the Run,” which will be playing concurrently at Film Forum — but it is with “The 400 Blows” that he most fully realized “the pulse” demanded of his chosen art. It’s an unsettling, intimate, and beautiful film well worth your reacquaintance.