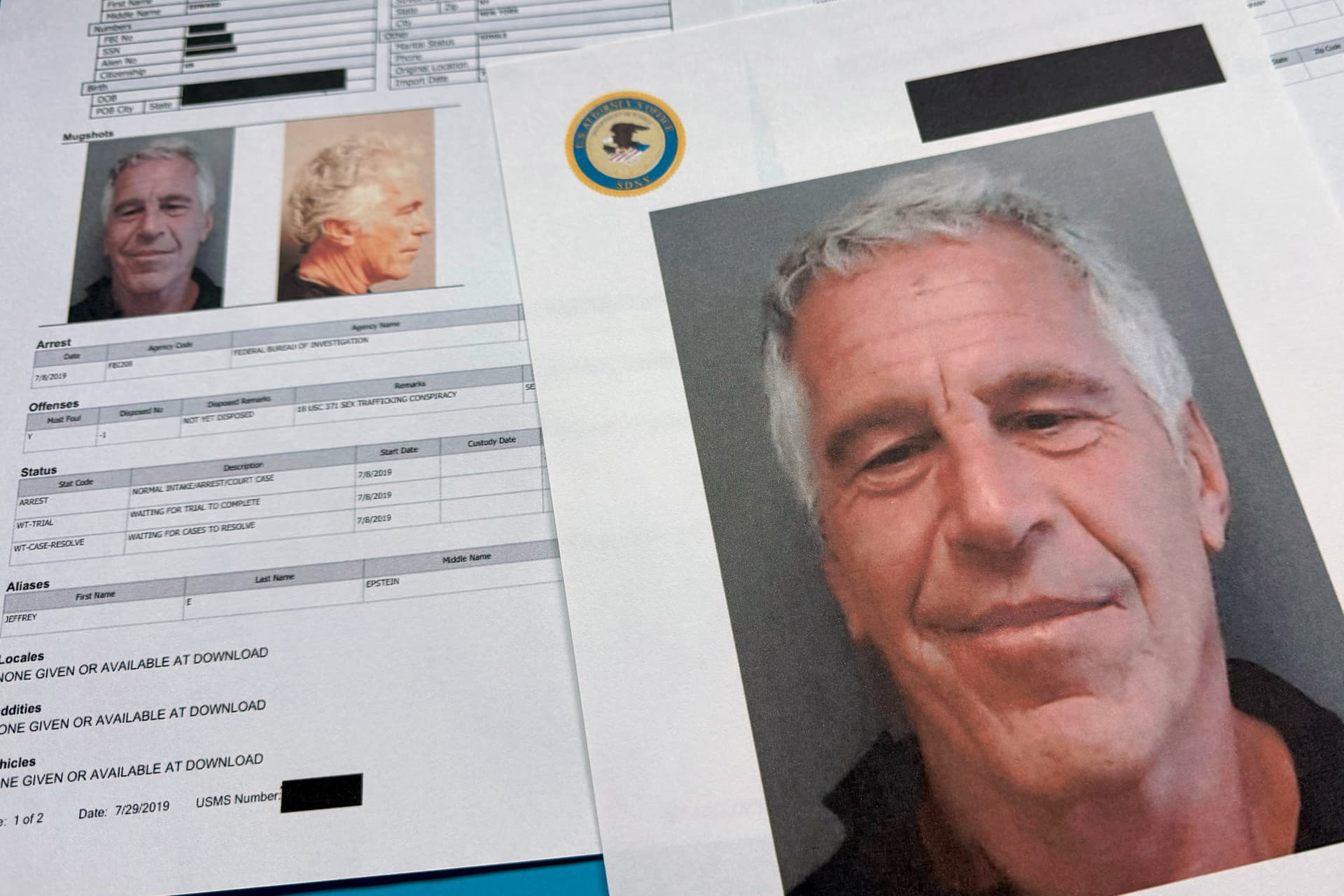

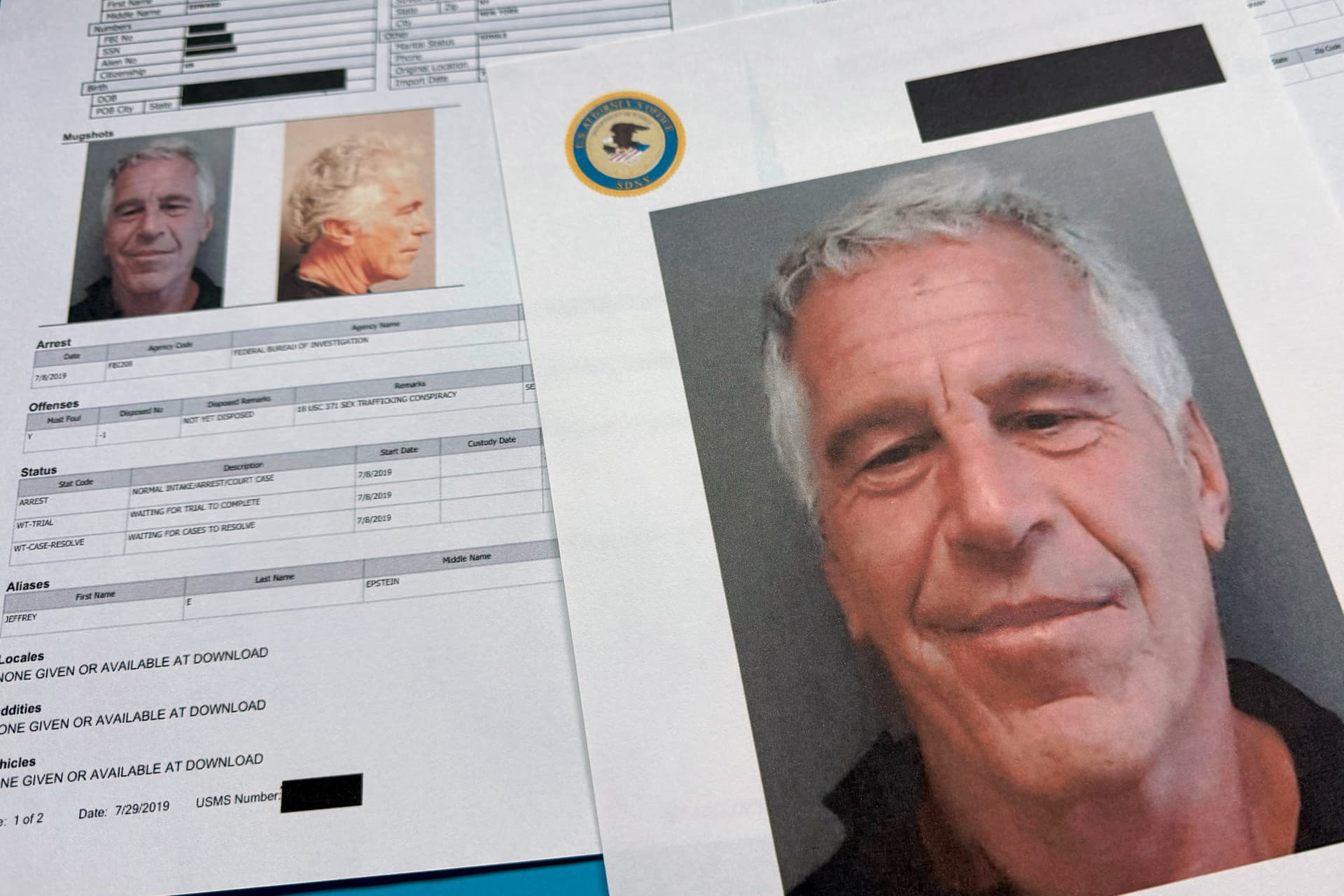

Final Release of Epstein Files Details Ties to Tech Titans and Top Officials but Fails To Satisfy Critics

By JOSEPH CURL

|The play’s breadth is what makes it so breathtaking. It’s about loving each other well. It’s about obligation and self-sufficiency and relationships, the intricacies of which are too complicated to name.

Already have a subscription? Sign in to continue reading

By JOSEPH CURL

|

By JAMES BROOKE

|

By CAROLINE McCAUGHEY

|$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

By continuing you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.